With the introduction of Office 2007, Microsoft changed the basic file format that underlies Word, PowerPoint and Excel. Instead of the proprietary and mostly undocumented format that ruled from Office 97 to Office 2003, Microsoft made a smart decision and switched to XML. This is tagged text, similar in structure and concept to HTML code with which you may already be familiar.

XML opens up a world of possibilities for automated document construction, but that’s a topic for another day. The everyday relevance for you and I is that if a Word or PowerPoint file isn’t doing what you need it to do and there are no tools in the program for the job, we can now dive in a edit the file ourselves. If you’re a point-and-click user, this is probably not thrilling. But if you’re a hacker at heart, a midnight coder or just a curious tinkerer, you can do some cool stuff.

The main tool you’re going to need is a text editor. While you can get away for a while with Notepad or TextEdit, those simple text editors don’t quite have the tools that get the job done efficiently. On Mac, I use BBEdit and on Windows I reach for Notepad++. BBEdit is reasonably-priced shareware and Notepad++ is freeware. They have a similar style of operation, so if you’re a cross-platform hacker it’s easy to switch between them. Notepad++ uses a plugin system, so you can add tools. For this job, you’re definitely going to want the free XML plugin. To install that, choose Plugins>Plugins Admin, scroll down the list to XML Tools, select it and click on Next. While you’re installing, aAnother very useful NotePad++ plugin is Compare.

The macOS requires somewhat more care with handling expanded Office files, or they won’t open after being rezipped. Please see this article for the best procedure on a Mac. The rest of this article mentions Windows methods, but the XML file structure is the same on both platforms.

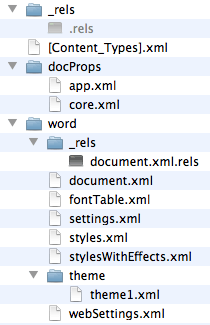

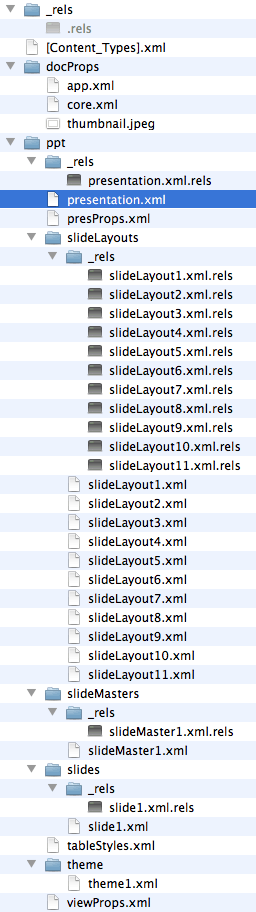

Word, Excel and PowerPoint files in the new format are actually simple Zip files with a different file ending. Getting into them couldn’t be easier: if you’re using Windows, add .zip to the end of the file (a copy of the file, if it’s anything important). You’ll get a warning from your OS, but you know what you’re doing! Now unzip it. Out pop several folders of XML, plus a top-level file or two.

Select one of the files and open it in your text editor. All the files have been linearized to minimize file size. This is where your XML tools come into play. In Notepad++, choose Plugins>XML Tools>Pretty Print (XML Only – with line breaks). Now you have a nicely indented, easy-to-read page to edit. When you’re done, it’s not necessary to re-linearize. Word, PowerPoint or Excel will do that for you later.

For people using Window’s built-in zip utility, there is an easy mistake to watch out for. By default, unzipping a file in Windows creates a new folder named for the file being expanded. If, when you’re re-assembling the file, you include this top-level folder, PowerPoint will raise an error about unreadable content in the presentation. To avoid this, first open the folder that Windows created. Select the _rels, docProps and ppt folders, plus the [Content_Types].xml file, then create a zip file from them.

As an alternative to unzipping/rezipping files in Windows, download the free 7-Zip utility. After installing, set your text editor as the 7-Zip editor. Then right-click on the Office file you want to edit and choose 7-Zip>Open Archive. A window opens showing the OOXML folders and files. Find the file you want to edit, right-click and choose Edit. Edit only 1 file at a time in 7-Zip, closing your text editor and updating the file each time. Otherwise, some or your changes may be lost.

XML hacking is useful for Excel or Word when you want to add additional color themes, lock graphics, or when you need to rescue a corrupt document. But it really shines with PowerPoint, allowing you to create custom table formats, extra custom colors that don’t fit into a theme, setting the default text size for tables and text boxes, and more. This technique separates the PowerPoint pros from the wannabes.

In my next post, I’ll get into the specifics of some cool XML hacking Office tricks. In the mean time, check out text editors and XML tools so you’re ready to hack!

If code editing isn’t your thing, we can do it for you! Email me at production@brandwares.com.

Hello

I tried a few changes, looks good, only for some xlsm I see bin files and a few one can not be exported (unzipped) , after rezipping the content I have a repair dialogbox and after repairing all seems to be ok.

Is there a way to force the unzipping of the primary BIN files ? Or do you know why such files can’t be unzipped ? May be protected ?

Thanks

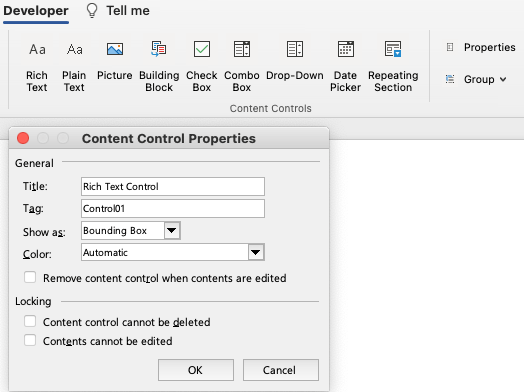

A .bin file is not a zip archive, it’s a binary file. It’s most likely a VBA macro, that’s the most common use of .bin files in Office XML. VBA can be edited using the program interface after you make the Developer tab visible.

I used the OOXML chrome plug in to edit the theme.xml file on my Mac. I downloaded the file and when I opened it in powerpoint, I got an error “PowerPoint found a problem with content in FS Powerpoint template_2018.potx. PowerPoint can attempt to repair the presentation.”

When I repair the presentation, all of the formatting is stripped out. Thoughts?

When you edited the XML, you introduced an error. It can be small, like an omitted quotation mark, or large, PowerPoint gives you the same error message. It’s small help, but the section that was removed was the part that had the mistake.

As mentioned in the article, because of Office’s uninformative feedback, it’s best to make one small change at a time, downloading and testing the file as you proceed. Once you gain experience and have a library of tested XML, it gets faster.

I’m trying to accomplish something that seems should be simple, but isn’t, to me. I want to remove the Style Gallery from the Word for Mac 16.24 tool bar. Is there a relatively straightforward way to do that?

Removing built-in controls is not only not simple, it’s not possible. The best you can do is hide the entire Styles group, but then you have no access to styles at all, because the Style Pane opener gets hidden as well. Word pros depend on styles to create consistent, professional documents and templates. I can recognize a Word newbie by the lack of style use in their documents. You might want to re-evaluate your urge to hide this very important control.

I’m writing an article about hacking Ribbon XML, but until that comes out, you might consider pruning the styles displayed in the Styles Gallery to just those that you use. Here’s my article showing how to do that: XML Hacking: Managing Styles

For an easier way to manage styles, please check out AuthorText Manage Styles, a free add-in from MVP Rich Michaels. It works both on macOS and Windows, a rarity in the world of Office add-ins.

Hi! I’m trying to unzip my presentation, however I’m getting the error message that windows cannot open the folder, and access to the compressed folder is denied. Any thoughts?

I haven’t seen that one. The steps on this page may help: [Fix] Compressed (Zipped) Folder Access Denied Error “Unable to Complete the Operation”. Best of luck!

Hi John,

I want to perform restriction in slides using PPT graphics. What I try to achieve is to allow users to edit PPT charts in the current template, but not to copy PPT charts outside the PowerPoint file. Is that something achievable using XML hacking or in any other way? Disabling copy and paste to the whole template, but still allowing edits, might be a viable alternative, if “no copy” is not possible for single object. I am using PowerPoint 2016.

Thanks!

That’s not possible with XML. If a chart is editable, it’s “copyable”.

There’s no simple way to disable the copy and paste commands using VBA, sorry.

xml code below cannot figure out how to resize to make notes section correctly formatted.

<?xml version=”1.0″ encoding=”UTF-8″ standalone=”yes”?>

<p:presentation xmlns:a=”http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/drawingml/2006/main” xmlns:r=”http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships” xmlns:p=”http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/presentationml/2006/main” saveSubsetFonts=”1″><p:sldMasterIdLst><p:sldMasterId id=”2147483648″ r:id=”rId1″/></p:sldMasterIdLst><p:notesMasterIdLst><p:notesMasterId r:id=”rId107″/></p:notesMasterIdLst><p:handoutMasterIdLst><p:handoutMasterId r:id=”rId108″/></p:handoutMasterIdLst><p:sldIdLst><p:sldId id=”256″ r:id=”rId2″/><p:sldId id=”257″ r:id=”rId3″/><p:sldId id=”258″ r:id=”rId4″/><p:sldId id=”259″ r:id=”rId5″/><p:sldId id=”260″ r:id=”rId6″/><p:sldId id=”271″ r:id=”rId7″/><p:sldId id=”261″ r:id=”rId8″/><p:sldId id=”299″ r:id=”rId9″/><p:sldId id=”272″ r:id=”rId10″/><p:sldId id=”262″ r:id=”rId11″/><p:sldId id=”263″ r:id=”rId12″/><p:sldId id=”264″ r:id=”rId13″/><p:sldId id=”265″ r:id=”rId14″/><p:sldId id=”266″ r:id=”rId15″/><p:sldId id=”267″ r:id=”rId16″/><p:sldId id=”355″ r:id=”rId17″/><p:sldId id=”356″ r:id=”rId18″/><p:sldId id=”357″ r:id=”rId19″/><p:sldId id=”269″ r:id=”rId20″/><p:sldId id=”273″ r:id=”rId21″/><p:sldId id=”274″ r:id=”rId22″/><p:sldId id=”275″ r:id=”rId23″/><p:sldId id=”276″ r:id=”rId24″/><p:sldId id=”277″ r:id=”rId25″/><p:sldId id=”278″ r:id=”rId26″/><p:sldId id=”279″ r:id=”rId27″/><p:sldId id=”280″ r:id=”rId28″/><p:sldId id=”281″ r:id=”rId29″/><p:sldId id=”282″ r:id=”rId30″/><p:sldId id=”284″ r:id=”rId31″/><p:sldId id=”286″ r:id=”rId32″/><p:sldId id=”287″ r:id=”rId33″/><p:sldId id=”367″ r:id=”rId34″/><p:sldId id=”292″ r:id=”rId35″/><p:sldId id=”368″ r:id=”rId36″/><p:sldId id=”293″ r:id=”rId37″/><p:sldId id=”294″ r:id=”rId38″/><p:sldId id=”295″ r:id=”rId39″/><p:sldId id=”296″ r:id=”rId40″/><p:sldId id=”297″ r:id=”rId41″/><p:sldId id=”298″ r:id=”rId42″/><p:sldId id=”300″ r:id=”rId43″/><p:sldId id=”326″ r:id=”rId44″/><p:sldId id=”301″ r:id=”rId45″/><p:sldId id=”302″ r:id=”rId46″/><p:sldId id=”303″ r:id=”rId47″/><p:sldId id=”304″ r:id=”rId48″/><p:sldId id=”305″ r:id=”rId49″/><p:sldId id=”313″ r:id=”rId50″/><p:sldId id=”315″ r:id=”rId51″/><p:sldId id=”314″ r:id=”rId52″/><p:sldId id=”306″ r:id=”rId53″/><p:sldId id=”307″ r:id=”rId54″/><p:sldId id=”309″ r:id=”rId55″/><p:sldId id=”311″ r:id=”rId56″/><p:sldId id=”308″ r:id=”rId57″/><p:sldId id=”310″ r:id=”rId58″/><p:sldId id=”312″ r:id=”rId59″/><p:sldId id=”348″ r:id=”rId60″/><p:sldId id=”350″ r:id=”rId61″/><p:sldId id=”349″ r:id=”rId62″/><p:sldId id=”351″ r:id=”rId63″/><p:sldId id=”344″ r:id=”rId64″/><p:sldId id=”328″ r:id=”rId65″/><p:sldId id=”345″ r:id=”rId66″/><p:sldId id=”347″ r:id=”rId67″/><p:sldId id=”343″ r:id=”rId68″/><p:sldId id=”323″ r:id=”rId69″/><p:sldId id=”325″ r:id=”rId70″/><p:sldId id=”324″ r:id=”rId71″/><p:sldId id=”341″ r:id=”rId72″/><p:sldId id=”332″ r:id=”rId73″/><p:sldId id=”327″ r:id=”rId74″/><p:sldId id=”329″ r:id=”rId75″/><p:sldId id=”331″ r:id=”rId76″/><p:sldId id=”330″ r:id=”rId77″/><p:sldId id=”333″ r:id=”rId78″/><p:sldId id=”334″ r:id=”rId79″/><p:sldId id=”335″ r:id=”rId80″/><p:sldId id=”336″ r:id=”rId81″/><p:sldId id=”337″ r:id=”rId82″/><p:sldId id=”338″ r:id=”rId83″/><p:sldId id=”339″ r:id=”rId84″/><p:sldId id=”352″ r:id=”rId85″/><p:sldId id=”342″ r:id=”rId86″/><p:sldId id=”353″ r:id=”rId87″/><p:sldId id=”360″ r:id=”rId88″/><p:sldId id=”358″ r:id=”rId89″/><p:sldId id=”364″ r:id=”rId90″/><p:sldId id=”365″ r:id=”rId91″/><p:sldId id=”366″ r:id=”rId92″/><p:sldId id=”359″ r:id=”rId93″/><p:sldId id=”361″ r:id=”rId94″/><p:sldId id=”362″ r:id=”rId95″/><p:sldId id=”346″ r:id=”rId96″/><p:sldId id=”316″ r:id=”rId97″/><p:sldId id=”317″ r:id=”rId98″/><p:sldId id=”321″ r:id=”rId99″/><p:sldId id=”318″ r:id=”rId100″/><p:sldId id=”319″ r:id=”rId101″/><p:sldId id=”340″ r:id=”rId102″/><p:sldId id=”320″ r:id=”rId103″/><p:sldId id=”322″ r:id=”rId104″/><p:sldId id=”354″ r:id=”rId105″/><p:sldId id=”363″ r:id=”rId106″/></p:sldIdLst><p:sldSz cx=”12192000″ cy=”6858000″/><p:notesSz cx=”6858000″ cy=”2962275″/><p:defaultTextStyle><a:defPPr><a:defRPr lang=”en-US”/></a:defPPr><a:lvl1pPr marL=”0″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl1pPr><a:lvl2pPr marL=”457200″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl2pPr><a:lvl3pPr marL=”914400″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl3pPr><a:lvl4pPr marL=”1371600″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl4pPr><a:lvl5pPr marL=”1828800″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl5pPr><a:lvl6pPr marL=”2286000″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl6pPr><a:lvl7pPr marL=”2743200″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl7pPr><a:lvl8pPr marL=”3200400″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl8pPr><a:lvl9pPr marL=”3657600″ algn=”l” defTabSz=”914400″ rtl=”0″ eaLnBrk=”1″ latinLnBrk=”0″ hangingPunct=”1″><a:defRPr sz=”1800″ kern=”1200″><a:solidFill><a:schemeClr val=”tx1″/></a:solidFill><a:latin typeface=”+mn-lt”/><a:ea typeface=”+mn-ea”/><a:cs typeface=”+mn-cs”/></a:defRPr></a:lvl9pPr></p:defaultTextStyle><p:extLst><p:ext uri=”{EFAFB233-063F-42B5-8137-9DF3F51BA10A}”><p15:sldGuideLst xmlns:p15=”http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/powerpoint/2012/main”/></p:ext><p:ext uri=”{2D200454-40CA-4A62-9FC3-DE9A4176ACB9}”><p15:notesGuideLst xmlns:p15=”http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/powerpoint/2012/main”/></p:ext></p:extLst></p:presentation>

You’re looking for p:notesSz. Your XML contains this:

It needs to be changed to this:

It’s easier to find by eye if you use a text editor that can prettify the XML to be humanly readable.

How do you change the default chart text size?

To set chart defaults, the simplest approach is to create a sample chart, then save it as a chart template. You can do this by right-clicking on sample chart and choosing Save as Template. The template will be saved into the Charts subfolder of your existing Office templates folder.

To distribute that template to others, create a Charts folder in their Office templates folder and copy the template into it. Then when users choose Insert>Chart, they should click on the Templates folder icon in the Chart Type dialog, then select the template. The chart will have Microsoft’s dummy data, as the template is not saved with the original sample chart data.

I found that not all pretty printing is corrected by PowerPoint. By extracting-pretty printing-zipping individual files in Default Template.potx, I was able to narrow it down to .\docProps\core.xml not playing nice.

On PPT 365 version 2311, I tried Notepad++ pretty print, as well as tidy from the command line. In each case, re-zipping the otherwise unchanged files to a POTX resulted in “PowerPoint found a problem with content in …, click Repair”.

Pretty printing any other file (incl. the .rels) did not trigger the repair warning on Default Template.potx.

Did anyone else observe this?

Using only Plugins>XML Tools>Pretty print in NotePad++, I can’t reproduce this problem. I didn’t recommend using Tidy in my article. If Tidy causes an issue, stay away from it.

Hi John! I have used this technique many times before but today I ran into an issue I haven’t seen before. I was making a PPT template for a company that needed some custom colors and I didn’t know this company uses PowerPoint on SharePoint a lot, and they say the custom colors row does not show AT ALL on SharePoint.

I can’t find a workaround or anything about this. Have you run into this or is there anything I can do to remedy this, or is there just no way to have Custom Colors show up on SharePoint?

Thanks for pointing this out. Unfortunately, SharePoint uses PowerPoint for the web, a light version of the program lacking many features. Custom colors do not display in the web edition, nor do they show in PowerPoint for iOS and Android. There is no workaround. Custom colors display in the desktop editions: PowerPoint for Windows and for Mac. I’ve updated the article with this information.

Hi John! Very excited about unlocking PPT features by hacking its XML. One question I had before purchasing your book – is it possible to modify the XML of a PPT during runtime (i.e: while the document is open by a user)?

If you mean changing the presentation size, you can do that by creating a SuperTheme that contains several different sizes in one file. The book covers how to create SuperThemes.

I rather meant adding / removing a shape for example. Is it possible to do this on an open PPT document?

Running programs lock the open file, prohibiting access to other processes. So usually the answer is no.

But if the file is open in PowerPoint, just use the program interface or a VBA macro to add or remove a shape. That’s much easier.

For everyone looking to get into OOXML Hacking in 2025:

There is a great Extension for Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code called “OOXML Viewer” that adds a lot of convenience!

If you open the folder containing your pptx file in VSCode, you can right-click on a pptx file and select “open OOXML package” and the extension will automatically extract and show the XML tree, format the XML to be readable for editing, and after you edit a file

and save, will repackage it back into the original pptx file.

I wrote about Visual Studio Code in my article OOXML Hacking: Editing in macOS. Rather than just installing the OOXML Viewer, instead look for the OOXML Extension Pack, which is a bundle of extensions that includes the Viewer.

For editing in Windows, I don’t find Visual Studio Code to have any advantage over using 7-Zip, but some might prefer the interface. For editing in macOS, it’s quite useful.